Variable types and examples

Introduction

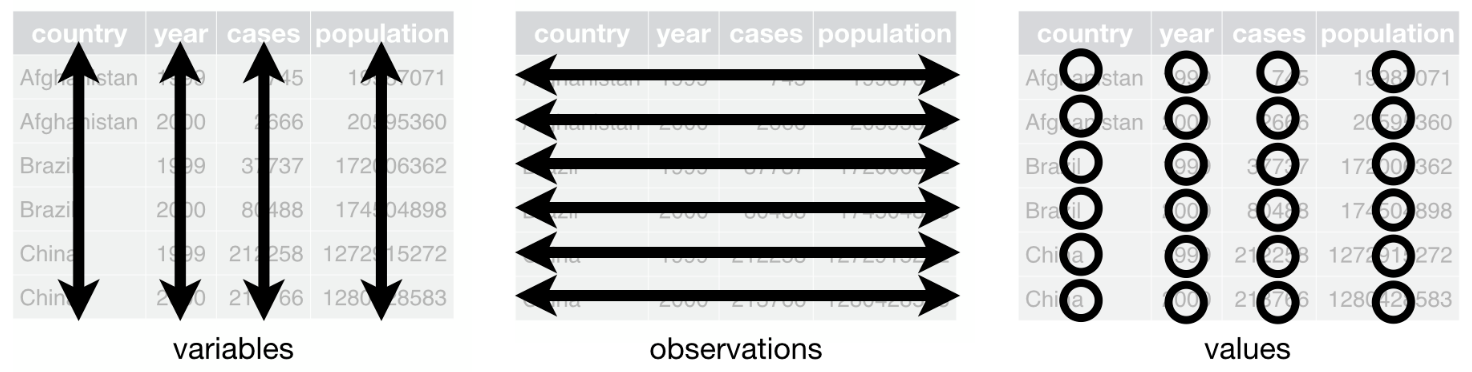

If you happen to work with datasets frequently, you probably know that each row of your dataset represents a different experimental unit (also called observation) and each column represents a different characteristic (called variable):

If you do some research on the weight and height of 100 students of your university, for example, you will most likely have a dataset containing 100 rows and 3 columns:

- one for the student’s ID (could be anonymized or not),

- one for the weight,

- and one for the height.

These three columns represent three characteristics of the 100 students. They are called variables.

In this article, we are going to focus on variables, and in particular on the different types of variable that exist in statistics. (To learn about the different data types in R, read “Data types in R”.)

Different types of variables for different types of statistical analysis

First, one may wonder why we are interested in defining the types of our variables of interest.

The reason why we often class variables into different types is because not all statistical analyses can be performed on all variable types. For instance, it is impossible to compute the mean of the variable “hair color” as you cannot sum brown and blond hair.

On the other hand, finding the mode of a continuous variable does not really make any sense because most of the time there will not be two exact same values, so there will be no mode. And even in the case there is a mode, there will be very few observations with this value. As an example, try finding the mode of the height of the students in your class. If you are lucky, a couple of students will have the same size. However, most of the time, every student will have a different size (especially if heights have been measured in millimeters) and thus there will be no mode. To see what kind of analysis is possible on each type of variable, see more details in the articles “Descriptive statistics by hand” and “Descriptive statistics in R”.

Similarly, some statistical tests can only be performed on certain type of variables. For example, the Pearson correlation is usually computed on two quantitative variables, while a Chi-square test of independence is done with two qualitative variables, and a Student t-test or ANOVA requires a mix of one quantitative and one qualitative variable.

Big picture

In statistics, variables are classified into 4 different types:

We present each type together with examples in the following sections.

Quantitative

A quantitative variable is a variable that reflects a notion of magnitude, that is, if the values it can take are numbers. A quantitative variable represents thus a measure and is numerical.

Quantitative variables are divided into two types: discrete and continuous. The difference is explained in the following two sections.

Discrete

Quantitative discrete variables are variables for which the values it can take are countable and have a finite number of possibilities. The values are often (but not always) integers. Here are some examples of discrete variables:

- Number of children per family

- Number of students in a class

- Number of citizens of a country

Even if it would take a long time to count the citizens of a large country, it is still technically doable. Moreover, for all examples, the number of possibilities is finite. Whatever the number of children in a family, it will never be 3.58 or 7.912 so the number of possibilities is a finite number and thus countable.

Continuous

On the other hand, quantitative continuous variables are variables for which the values are not countable and have an infinite number of possibilities. For example:

- Age

- Weight

- Height

For simplicity, we usually referred to years, kilograms (or pounds) and centimeters (or feet and inches) for age, weight and height respectively. However, a 28-year-old man could actually be 28 years, 7 months, 16 days, 3 hours, 4 minutes, 5 seconds, 31 milliseconds, 9 nanoseconds old.

For all measurements, we usually stop at a standard level of granularity, but nothing (except our measurement tools) prevents us from going deeper, leading to an infinite number of potential values. The fact that the values can take an infinite number of possibilities makes it uncountable.

Qualitative

In opposition to quantitative variables, qualitative variables (also referred as categorical variables or factors in R) are variables that are not numerical and which values fit into categories.

In other words, a qualitative variable is a variable which takes as its values modalities, categories or even levels, in contrast to quantitative variables which measure a quantity on each individual.

Qualitative variables are divided into two types: nominal and ordinal.

Nominal

A qualitative nominal variable is a qualitative variable where no ordering is possible or implied in the levels.

For example, the variable gender is nominal because there is no order in the levels (no matter how many levels you consider for the gender—only two with female/male, or more than two with female/male/ungendered/others, levels are unordered). Eye color is another example of a nominal variable because there is no order among blue, brown or green eyes.

A nominal variable can have:

- two levels (e.g., do you smoke? Yes/No, or are you pregnant? Yes/No), or

- a large number of levels (what is your college major? Each major is a level in that case).

Note that a qualitative variable with exactly 2 levels is also referred as a binary or dichotomous variable.

Ordinal

On the other hand, a qualitative ordinal variable is a qualitative variable with an order implied in the levels. For instance, if the severity of road accidents has been measured on a scale such as light, moderate and fatal accidents, this variable is a qualitative ordinal variable because there is a clear order in the levels.

Another good example is health, which can take values such as poor, reasonable, good, or excellent. Again, there is a clear order in these levels so health is in this case a qualitative ordinal variable.

Variable transformations

There are two main variable transformations:

- From a continuous to a discrete variable

- From a quantitative to a qualitative variable

From continuous to discrete

Let’s say we are interested in babies’ ages. The data collected is the age of the babies, so a quantitative continuous variable. However, we may work with only the number of weeks since birth and thus transforming the age into a discrete variable. The variable age remains a quantitative continuous variable but the variable we are working on (i.e., the number of weeks since birth) can be seen as a quantitative discrete variable.

From quantitative to qualitative

Let’s say we are interested in the Body Mass Index (BMI). For this, a researcher collects data on height and weight of individuals and computes the BMI. The BMI is a quantitative continuous variable but the researcher may want to turn it into a qualitative variable by categorizing individuals below a certain threshold as underweighted, above a certain threshold as overweighted and the rest as normal weighted. The raw BMI is a quantitative continuous variable but the categorization of the BMI makes the transformed variable a qualitative (ordinal) variable, where the levels are in this case underweighted < normal < overweighted.

Same goes for age when age is transformed to a qualitative ordinal variable with levels such as minors, adults and seniors. It is also often the case (especially in surveys) that the variable salary (quantitative continuous) is transformed into a qualitative ordinal variable with different range of salaries (e.g., < 1000€, 1000 - 2000€, > 2000€).

Additional notes

Misleading data encoding

Last but not least, in datasets it is very often the case that numbers are used for qualitative variables. For instance, a researcher may assign the number “1” to women and the number “2” to men (or “0” to the answer “No” and “1” to the answer “Yes”). Despite the numerical classification, the variable gender is still a qualitative variable and not a discrete variable as it may look. The numerical classification is only used to facilitate data collection and data management. It is indeed easier to write the number “1” or “2” instead of “women” or “men”, and thus less prone to encoding errors.

The same goes for the identification of each observation. Suppose you collected information on 100 students. You may use their student’s ID to identify them in the dataset (so that you can trace them back). Most of the time, students’ ID (or ID in general) are encoded as numeric values. At first sight, it may thus look like a quantitative variable (because it goes from 1 to 100 for example). However, ID is clearly not a quantitative variable because it actually corresponds to an anonymized version of the student’s first and last name. If you think about it, it would make no sense to compute the mean or median on the IDs, as it does not represent a numerical measurement (but rather just an easier way to identify students than with their names).

If you face this kind of setup, do not forget to transform your variable into the right type before performing any statistical analyses. Usually, a basic descriptive analysis (and knowledge about the variables which have been measured) prior to the main statistical analyses is enough to check that all variable types are correct.

Conclusion

Thanks for reading.

I hope this article helped you to understand the different types of variable. If you would like to learn more about the different data types in R, read the article “Data types in R”.

As always, if you have a question or a suggestion related to the topic covered in this article, please add it as a comment so other readers can benefit from the discussion.

Liked this post?

- Get updates every time a new article is published (no spam and unsubscribe anytime)

- Support the blog

- Share on: