Chi-square test of independence in R

Introduction

This article explains how to perform the Chi-square test of independence in R and how to interpret its results. To learn more about how the test works and how to do it by hand, I invite you to read the article “Chi-square test of independence by hand”.

To briefly recap what have been said in that article, the Chi-square test of independence tests whether there is a relationship between two categorical variables. The null and alternative hypotheses are:

- \(H_0\) : the variables are independent, there is no relationship between the two categorical variables. Knowing the value of one variable does not help to predict the value of the other variable

- \(H_1\) : the variables are dependent, there is a relationship between the two categorical variables. Knowing the value of one variable helps to predict the value of the other variable

The Chi-square test of independence works by comparing the observed frequencies (so the frequencies observed in your sample) to the expected frequencies if there was no relationship between the two categorical variables (so the expected frequencies if the null hypothesis was true).

Data

For our example, let’s reuse the dataset introduced in the article “Descriptive statistics in R”. This dataset is the well-known iris dataset slightly enhanced. Since there is only one categorical variable and the Chi-square test of independence requires two categorical variables, we add the variable size which corresponds to small if the length of the petal is smaller than the median of all flowers, big otherwise:

dat <- iris

dat$size <- ifelse(dat$Sepal.Length < median(dat$Sepal.Length),

"small", "big"

)We now create a contingency table of the two variables Species and size with the table() function:

table(dat$Species, dat$size)##

## big small

## setosa 1 49

## versicolor 29 21

## virginica 47 3The contingency table gives the observed number of cases in each subgroup. For instance, there is only one big setosa flower, while there are 49 small setosa flowers in the dataset.

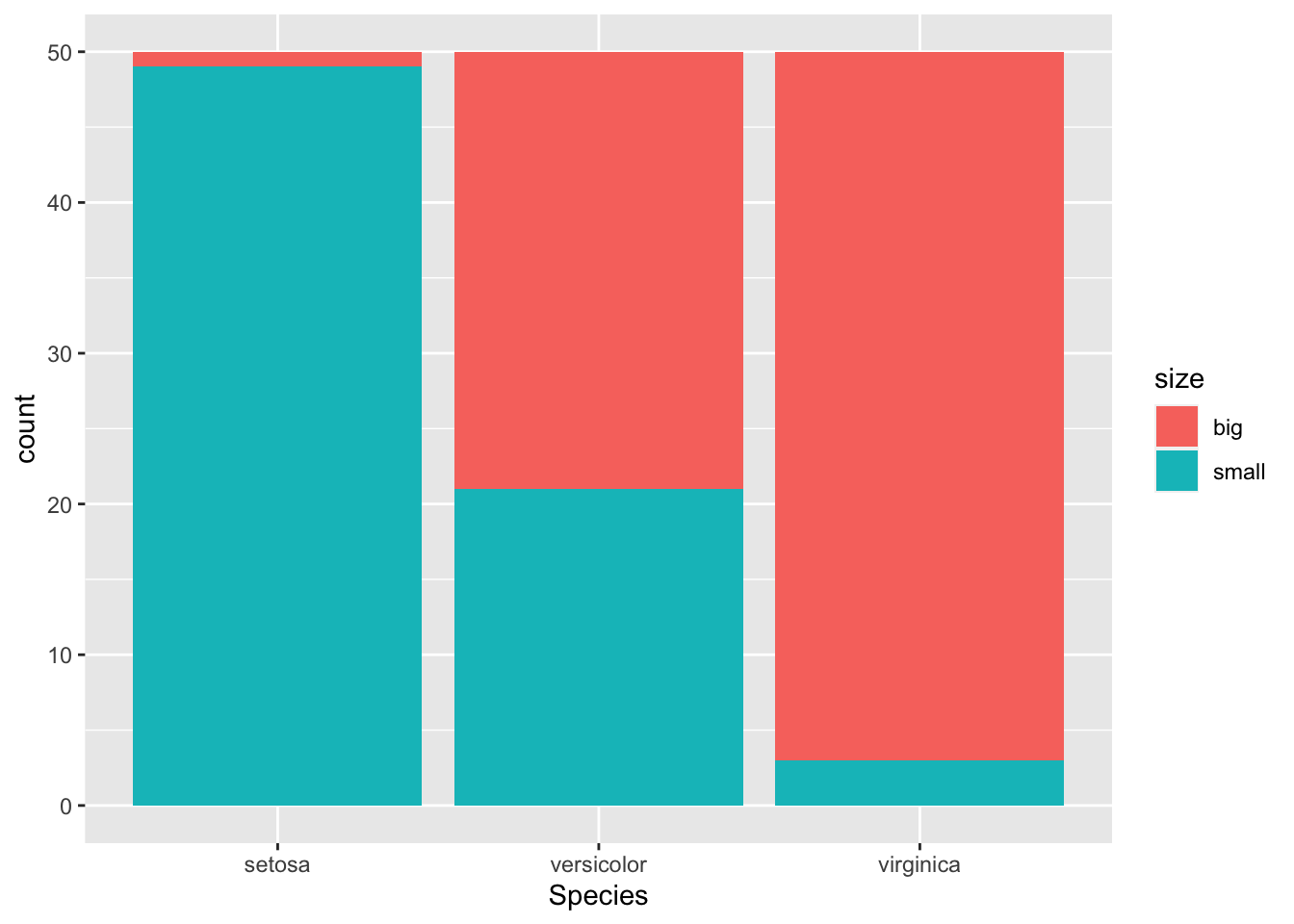

It is also a good practice to draw a barplot to visually represent the data:

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(dat) +

aes(x = Species, fill = size) +

geom_bar()

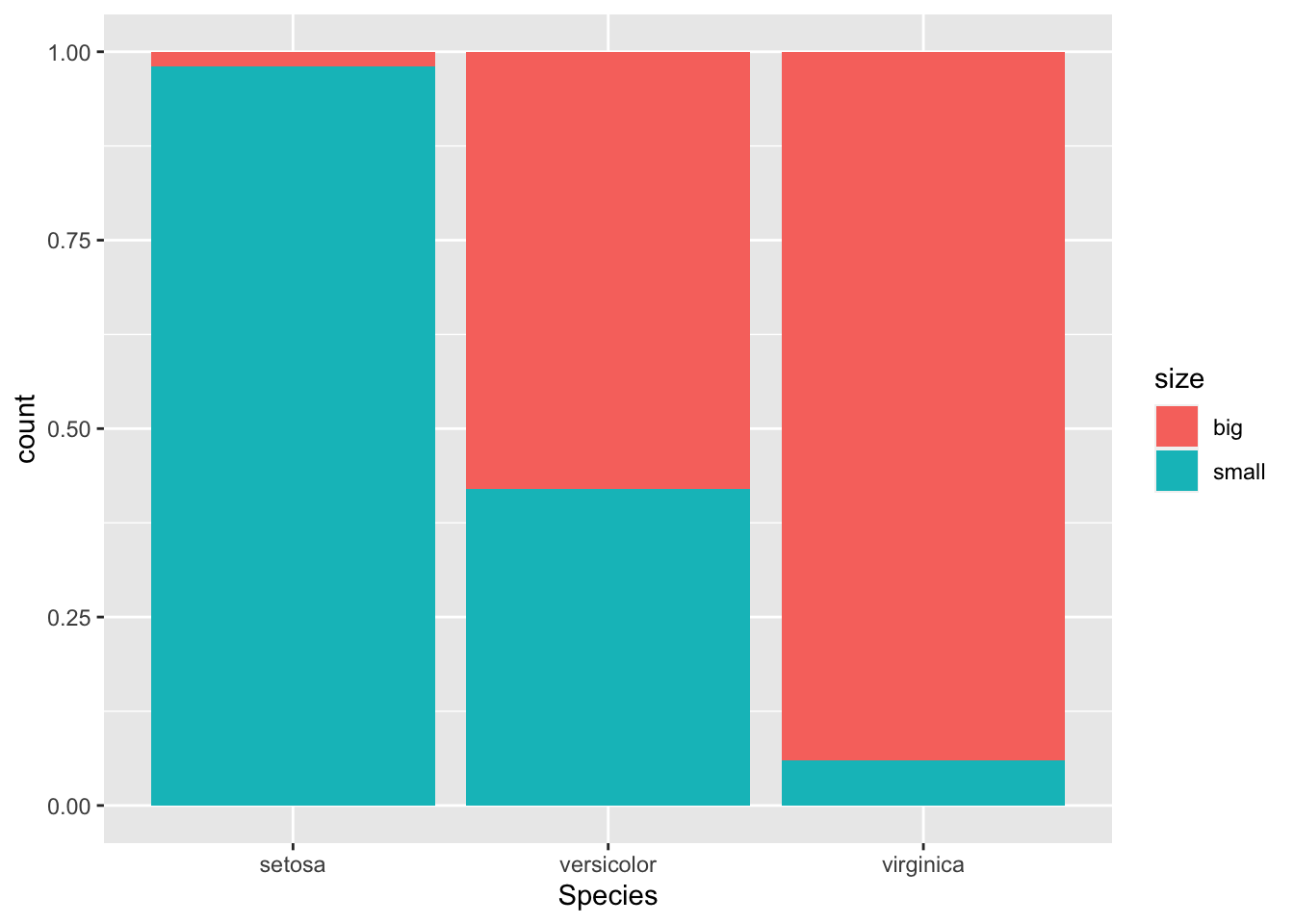

If you prefer to visualize it in terms of proportions (so that bars all have a height of 1, or 100%):

ggplot(dat) +

aes(x = Species, fill = size) +

geom_bar(position = "fill")

This second barplot is particularly useful if there are a different number of observations in each level of the variable drawn on the \(x\)-axis because it allows to compare the two variables on the same ground.

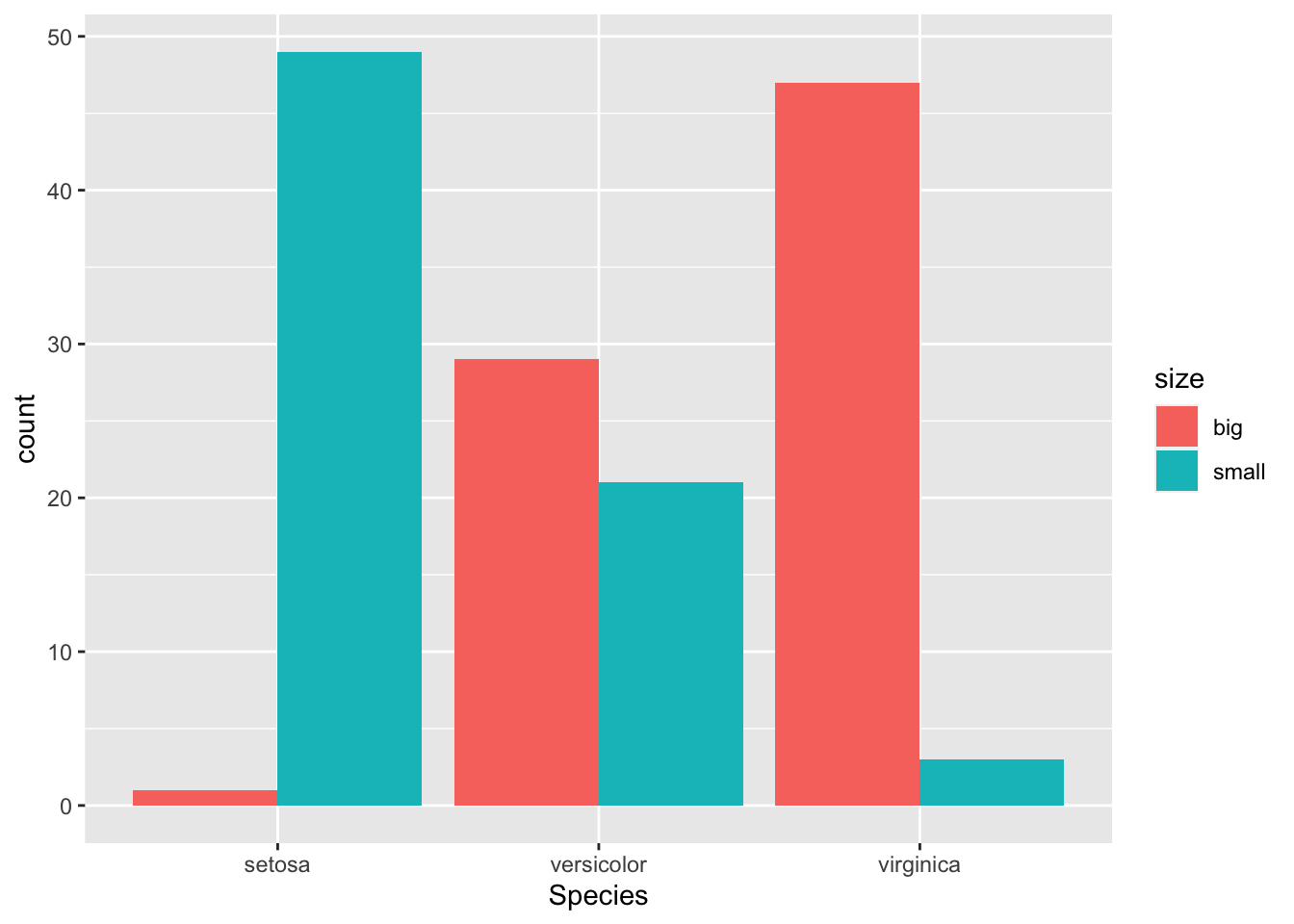

If you prefer to have the bars next to each other:

ggplot(dat) +

aes(x = Species, fill = size) +

geom_bar(position = "dodge")

See the article “Graphics in R with ggplot2” to learn how to create this kind of barplot in {ggplot2}.

Chi-square test of independence in R

For this example, we are going to test in R if there is a relationship between the variables Species and size. For this, the chisq.test() function is used:

test <- chisq.test(table(dat$Species, dat$size))

test##

## Pearson's Chi-squared test

##

## data: table(dat$Species, dat$size)

## X-squared = 86.035, df = 2, p-value < 2.2e-16Everything you need appears in this output:

- the title of the test,

- which variables have been used,

- the test statistic,

- the degrees of freedom and

- the \(p\)-value of the test.

You can also retrieve the \(\chi^2\) test statistic and the \(p\)-value with:

test$statistic # test statistic## X-squared

## 86.03451test$p.value # p-value## [1] 2.078944e-19If you need to find the expected frequencies, use test$expected.

If a warning such as “Chi-squared approximation may be incorrect” appears, it means that the smallest expected frequencies is lower than 5. To avoid this issue, you can either:

- gather some levels (especially those with a small number of observations) to increase the number of observations in the subgroups, or

- use the Fisher’s exact test

The Fisher’s exact test does not require the assumption of a minimum of 5 expected counts in the contingency table. It can be applied in R thanks to the function fisher.test(). This test is similar to the Chi-square test in terms of hypothesis and interpretation of the results. Learn more about this test in this article dedicated to this type of test.

Talking about assumptions, the Chi-square test of independence requires that the observations are independent. This is usually not tested formally, but rather verified based on the design of the experiment and on the good control of experimental conditions. If you are not sure, ask yourself if one observation is related to another (if one observation has an impact on another). If not, it is most likely that you have independent observations.

If you have dependent observations (paired samples), the McNemar’s or Cochran’s Q tests should be used instead. The McNemar’s test is used when we want to know if there is a significant change in two paired samples (typically in a study with a measure before and after on the same subject) when the variables have only two categories. The Cochran’s Q tests is an extension of the McNemar’s test when we have more than two related measures.

For your information, there are three other methods to perform the Chi-square test of independence in R:

- with the

summary()function - with the

assocstats()function from the{vcd}package - with the

ctable()function from the{summarytools}package

# second method:

summary(table(dat$Species, dat$size))## Number of cases in table: 150

## Number of factors: 2

## Test for independence of all factors:

## Chisq = 86.03, df = 2, p-value = 2.079e-19# third method:

library(vcd)

assocstats(table(dat$Species, dat$size))## X^2 df P(> X^2)

## Likelihood Ratio 107.308 2 0

## Pearson 86.035 2 0

##

## Phi-Coefficient : NA

## Contingency Coeff.: 0.604

## Cramer's V : 0.757library(summarytools)

library(dplyr)

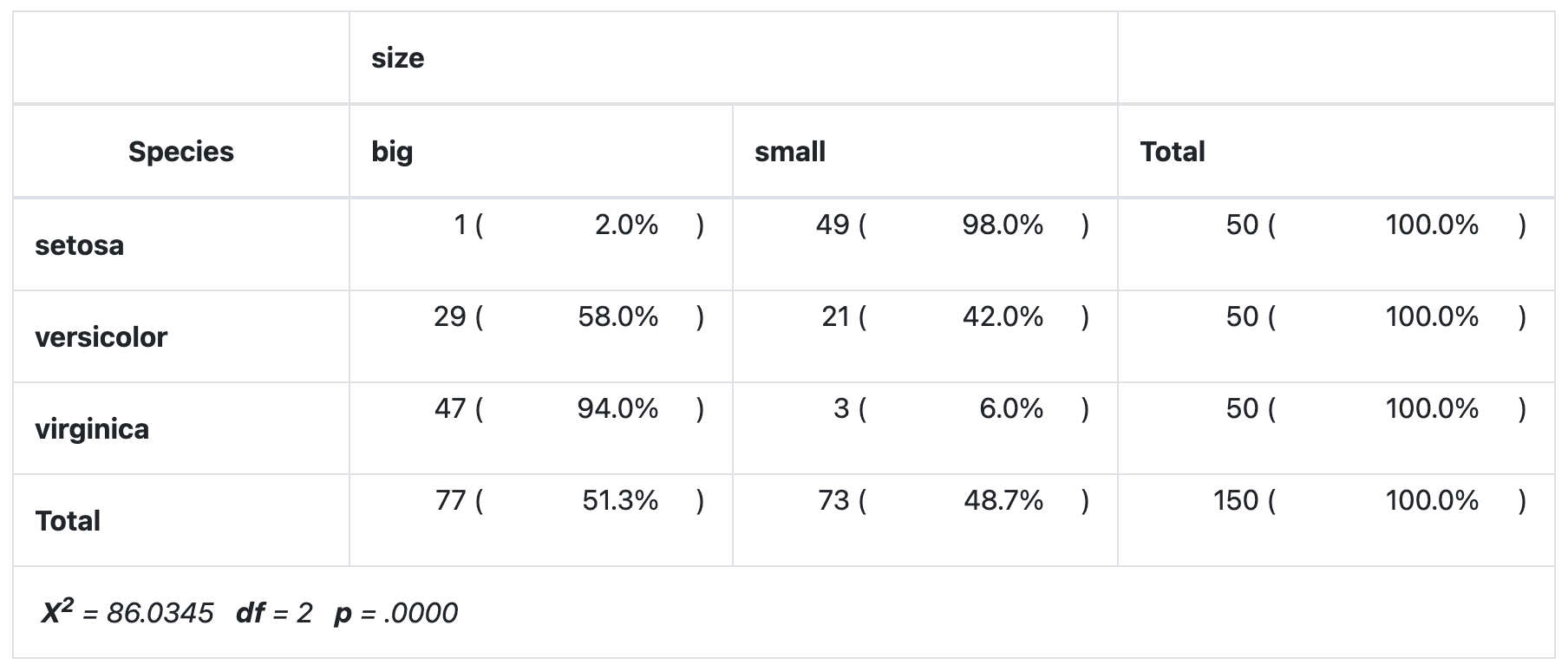

# fourth method:

dat %$%

ctable(Species, size,

prop = "r", chisq = TRUE, headings = FALSE

) %>%

print(

method = "render",

style = "rmarkdown",

footnote = NA

)

As you can see all four methods give the same results.

If you do not have the same p-values with your data across the different methods, make sure to add the correct = FALSE argument in the chisq.test() function to prevent from applying the Yate’s continuity correction, which is applied by default in this method.1

Conclusion and interpretation

From the output and from test$p.value we see that the \(p\)-value is less than the significance level of 5%. Like any other statistical test, if the \(p\)-value is less than the significance level, we can reject the null hypothesis. If you are not familiar with \(p\)-values, I invite you to read this section.

\(\Rightarrow\) In our context, rejecting the null hypothesis for the Chi-square test of independence means that there is a significant relationship between the species and the size. Therefore, knowing the value of one variable helps to predict the value of the other variable.

Combination of plot and statistical test

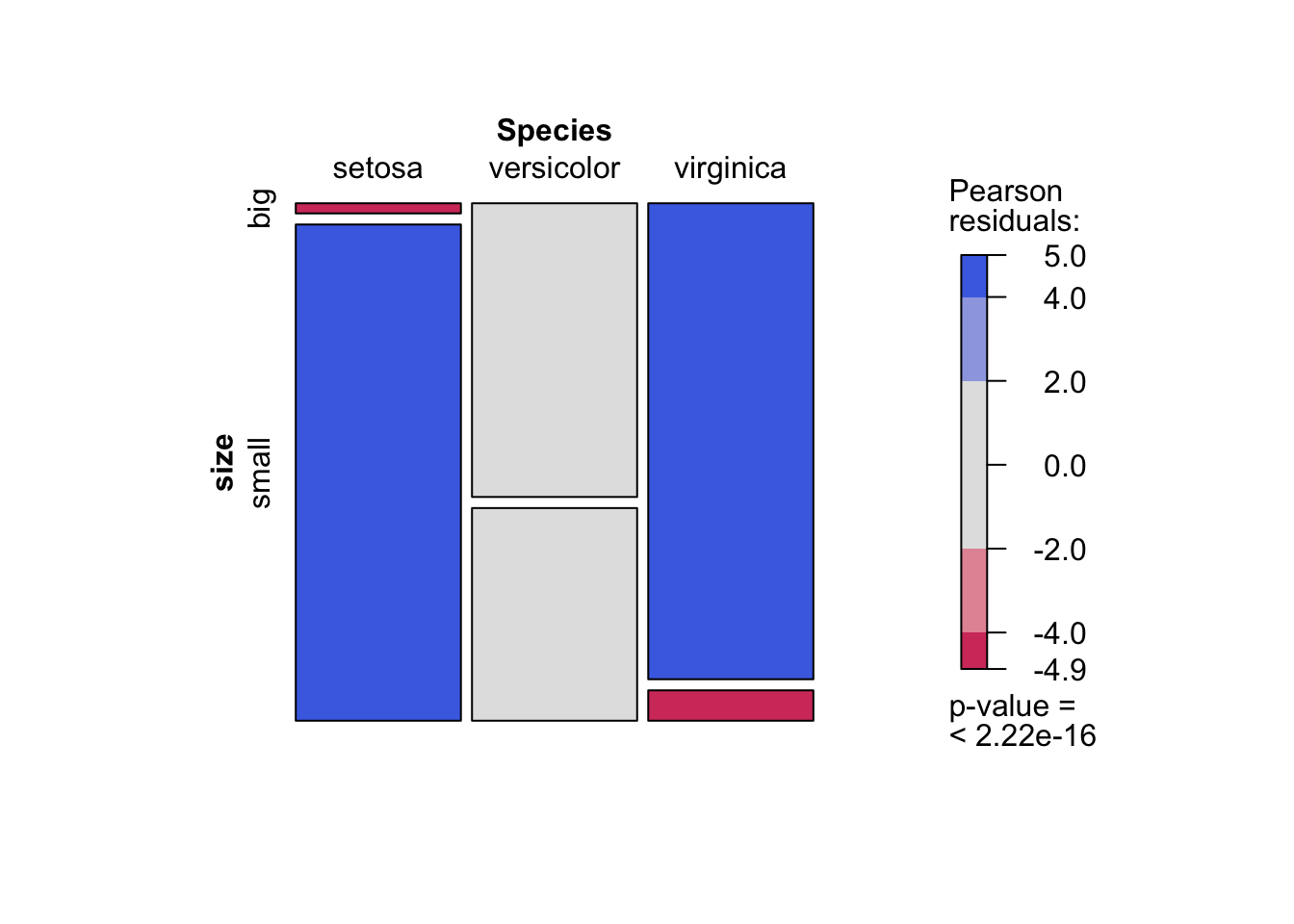

I recently discovered the mosaic() function from the {vcd} package. This function has the advantage that it combines a mosaic plot (to visualize a contingency table) and the result of the Chi-square test of independence:

library(vcd)

mosaic(~ Species + size,

direction = c("v", "h"),

data = dat,

shade = TRUE

)

As you can see, the mosaic plot is similar to the barplot presented above, but the p-value of the Chi-square test is also displayed at the bottom right.

Moreover, this mosaic plot with colored cases shows where the observed frequencies deviates from the expected frequencies if the variables were independent. The red cases means that the observed frequencies are smaller than the expected frequencies, whereas the blue cases means that the observed frequencies are larger than the expected frequencies.

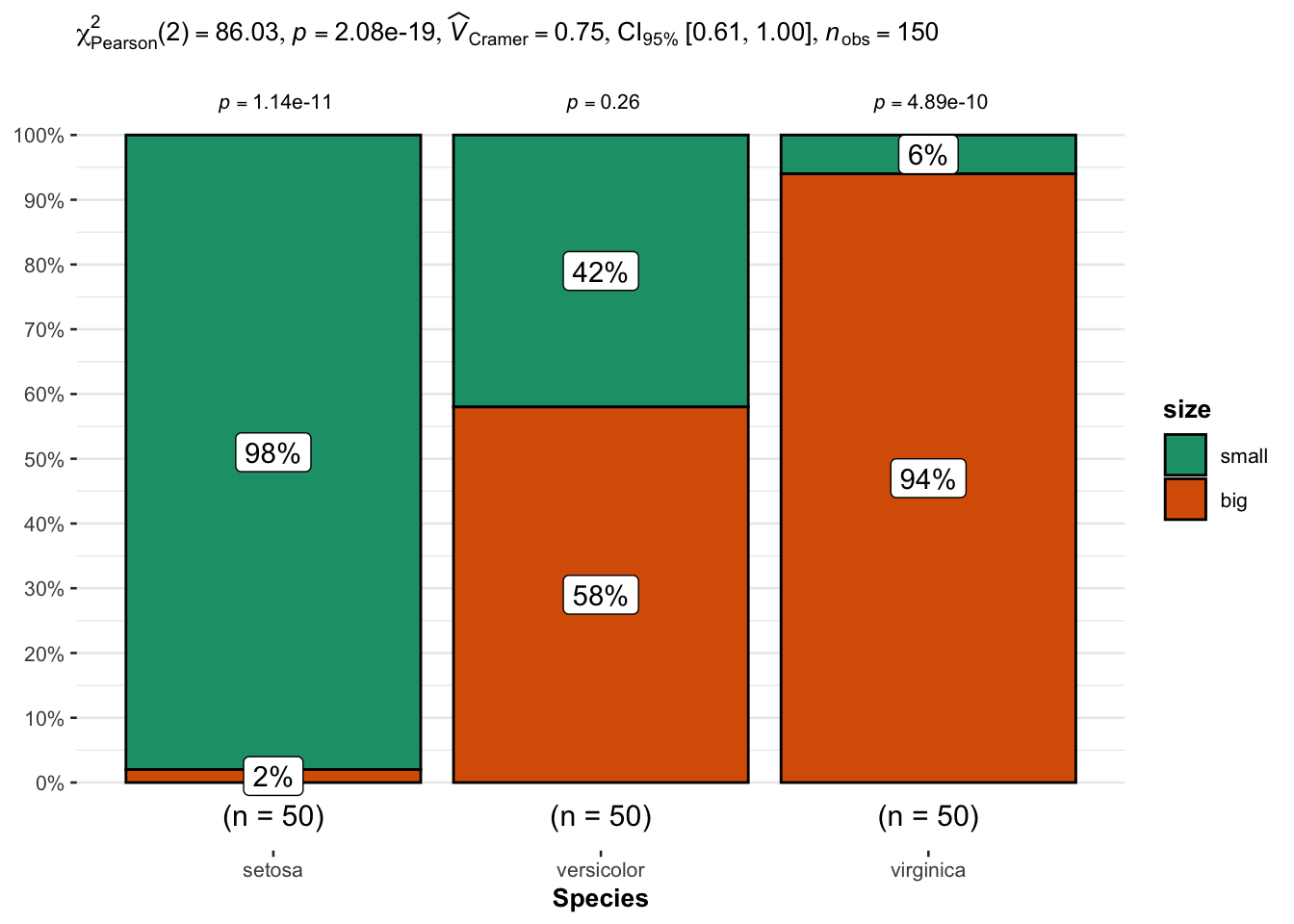

An alternative is the ggbarstats() function from the {ggstatsplot} package:

# load packages

library(ggstatsplot)

library(ggplot2)

# plot

ggbarstats(

data = dat,

x = size,

y = Species

) +

labs(caption = NULL) # remove caption

From the plot, it seems that big flowers are more likely to belong to the virginica species, while small flowers tend to belong to the setosa species. Species and size are thus expected to be dependent.

This is confirmed thanks to the statistical results displayed in the subtitle of the plot. There are several results, but we can in this case focus on the \(p\)-value which is displayed after p = at the top (in the subtitle of the plot).

As with the previous tests, we reject the null hypothesis and we conclude that species and size are dependent (\(p\)-value < 0.001).

Thanks for reading. I hope the article helped you to perform the Chi-square test of independence in R and interpret its results. If you would like to learn how to do this test by hand and how it works, read the article “Chi-square test of independence by hand”. If you want to go further and estimate the strength of the relationship between two categorical variables, see the binary logistic regression.

As always, if you have a question or a suggestion related to the topic covered in this article, please add it as a comment so other readers can benefit from the discussion.

(Note that this article is available for download on my Gumroad page.)

Thanks Herivelto for pointing it out.↩︎

Liked this post?

- Get updates every time a new article is published (no spam and unsubscribe anytime):