Koh-Lanta 2022: the ambassadors probability problem

Introduction

There is a popular TV show broadcasted in France and the french-speaking part of Belgium called “Koh-Lanta”.

In this show, several adventurers are dropped off on a desert island with almost no food nor equipment (just a personal backpack with their clothes and a small portion of rice). They must learn to survive on the hostile island by building their hut, finding water and food, etc.

Each season, adventurers are divided into teams (called tribes), and the teams compete against each other in games involving ability, strength, thinking and endurance. Every other game, the winning tribe receives some food or survival equipment (something to fish or something to make a fire, for instance). The losing tribe receives nothing. For the other half of the games, each member of the losing tribe has to elect an adventurer. The adventurer with the most votes leaves the show definitely. The winning tribe goes back to its island with all of its members.

At some point during the show, the two competing tribes are grouped together into one single tribe, and it continues this time with each adventurer competing against each other (so they play individually). The winner of the show is the last one to “survive”.

The 2022 season started with 24 adventurers. Just before being grouped together, each tribe has to select an adventurer in the opposing tribe. The two selected adventurers become ambassadors of their tribe. The two ambassadors must then go to another island in order to choose the adventurer who is going to leaves the show definitely. The adventurer selected by the two ambassadors will not be part of the reunification of the two tribes and her adventure stops there.

Of course, both ambassadors want to eliminate a member of the opposing tribe (to arrive at the reunification with the most allies). If the two ambassadors cannot agree, they have to play a game that will determine which of the 2 ambassadors must leave the show. This game is entirely based on luck. For the rest of the article, we call this game the ambassadors’ game.

Before 2022

Here were the rules of the ambassadors’ game before the 2022 season:

There are two identical urns, one in front of each ambassador. Each urn contains exactly one black ball and one white ball. Each ambassador has to draw a ball among the 2 from his urn. Both urns are of course closed, so no one sees which ball is picked (nor which one is not picked). The winner of the game (remember that the winner stays in the show, the loser has to leave definitely) is the one who picks a white ball while the other ambassador draws a black ball. If both ambassadors draw the same ball (both black or both white), the balls are put back in the urns and the game start over (with the exact same conditions) until the two ambassadors draw a ball of different color.

For each draw, there are thus four possible results:

- Ambassador from tribe A draws a white ball and ambassador from tribe B draws a black ball: ambassador from tribe A wins.

- Ambassador from tribe A draws a black ball and ambassador from tribe B draws a white ball: ambassador from tribe B wins.

- Both ambassadors draw a black ball: the game start over.

- Both ambassadors draw a white ball: the game start over.

Let’s compute the probability for each result to occur. Since the two events are independent (the fact that ambassador A draws a white ball does not change the probability for ambassador B to draw a white ball makes the two events independent), we can multiply the probabilities to compute the joint probability of the two events.

With \(P_A\) (\(P_B\)) denoting the probability that ambassador from tribe A (B) draws a white ball, we have:

- \(P_A \cdot (1 - P_B) = 0.5 \cdot 0.5 = 0.25\)

- \((1 - P_A) \cdot P_B = 0.5 \cdot 0.5 = 0.25\)

- \((1 - P_A) \cdot (1 - P_B) = 0.5 \cdot 0.5 = 0.25\)

- \(P_A \cdot P_B = 0.5 \cdot 0.5 = 0.25\)

The sum of the 4 probabilities gives 1 (i.e., 100%), which makes sense since it covers all possible outcomes.

This means that, on the first draw, each ambassador has a probability of 25% to win the game (outcome 1 for ambassador A, outcome 2 for ambassador B).

Of course, since the game is repeated until there is a winner, probabilities for outcomes 3 and 4 tend, in the long run, to decrease until it becomes null (0%). If this statement is not straightforward to you, think about it like this: if you play that game with your friend up to 100 times, what is the probability that there is still no winner, meaning that you and your friend drew the same ball (never a different color) 100 times in a row. You conceive that it is highly unlikely.

In this context, since both urns are identical and the game is played indefinitely until there is a winner, ambassadors have exactly the same probability of winning that game. It is indeed a 50-50 chance for each of them.

In 2022

Of course, I would not write an article about that ambassadors’ game if it is was this easy and straightforward.

The 2022 season differs from the previous ones in the sense that for each game, the losing tribe receives an additional punishment (called a curse in the show). As a consequence, this year, the two urns at the ambassadors’ game were not identical.

To give you some context, the red tribe won against the yellow tribe in the last game before the ambassadors’ negotiation. The punishment for the yellow tribe was the following:

- The yellow tribe (with its ambassador Colin) had an urn with 2 black balls and 1 white ball.

- The red tribe (with its ambassador Louana) had an urn with 1 black ball and 1 white ball.

This is indeed a punishment for the yellow tribe since the game is not fair anymore: the ambassador of the red tribe clearly has a higher chance of winning that game compared to the ambassador of the yellow tribe.

For the curious among you, here is how it happened:

- The two ambassadors were informed by the presenter Denis Brogniart about the composition of the urns for each tribe.

- Knowing that the odds were not in his favour, Colin (ambassador of the yellow tribe), chose not to play the game.1

- They finally agreed on the name of the adventurer who would leave the show (an adventurer of the yellow tribe).

You guessed it by now, the reason for writing this article is of course not to explain you what actually happened—the news sites do it better and much faster than me. The reason is that I wanted to compute the chance of winning the game for each ambassador if they had not agreed on an adventurer to eliminate.2

Moreover, I wanted to compute these probabilities in R through simulation. And why not, reuse the code in case organizers of Koh-Lanta decide to change the rules again in the future.

Even if you do not watch Koh-Lanta (because it is not broadcasted in your country, or you do not like the show), it could be of interest to those of you who want to see:

- how a real life example can be transferred into R,

- and how a

for loopand a function can be used to answer the initial question.

Probabilities computation in R

For the remaining of this article, we denote:

- \(p_c\), the probability that Colin (ambassador of the yellow tribe) draws a white ball,

- \(p_l\), the probability that Louana (ambassador of the red tribe) draws a white ball,

- \(q_c\), the probability that Colin draws a black ball,

- \(q_l\), the probability that Louana draws a black ball.

Based on the composition of the urns given by Denis Brogniart, we have:

p_c <- 1 / 3

p_l <- 1 / 2

q_c <- (1 - p_c)

q_l <- (1 - p_l)First draw

To start easy, let’s first compute the winning probabilities for each ambassador on the first draw only. Remember that to have a winner, balls must be of different colors.

Louana wins if and only if Colin draws a black ball and Louana draws a white ball:

# Louana winning on first draw

l_win <- q_c * p_l

l_win## [1] 0.3333333Louana has a 33.33% chance of winning on the first draw.

On the other hand, Colin wins if and only if Louana draws a black ball and Colin draws a white ball:

# Colin winning on first draw

c_win <- q_l * p_c

c_win## [1] 0.1666667Colin has a 16.67% chance of winning on the first draw.

You can already see that the game is in favour of Louana, as expected. Let’s see now how it evolves when playing several times.

Second draw

To win exactly on the second draw, it must be a tie on the first draw.

# Louana winning on second draw

tie <- (p_c * p_l) + (q_c * q_l)

l_win2 <- tie * l_win

l_win2## [1] 0.1666667# Colin winning on second draw

c_win2 <- tie * c_win

c_win2## [1] 0.08333333- Louana has a 16.67% chance of winning on the second draw.

- Colin has a 8.33% chance of winning on the second draw.

Third draw

To win exactly on the third draw, it must be a tie on the first two draws.

# Louana winning on third draw

l_win3 <- (tie^2) * l_win

l_win3## [1] 0.08333333# Colin winning on third draw

c_win3 <- (tie^2) * c_win

c_win3## [1] 0.04166667- Louana has a 8.33% chance of winning on the third draw.

- Colin has a 4.17% chance of winning on the third draw.

A pattern seems to emerge in the code.

Game limited to 3 draws

We can already compute the probabilities of winning for each ambassador as if the game was limited to three draws, by summing the probabilities for each of the first three draws:

# Louana winning on draw 1, 2 or 3

l_win_tot <- l_win + l_win2 + l_win3

l_win_tot## [1] 0.5833333# Colin winning on draw 1, 2 or 3

c_win_tot <- c_win + c_win2 + c_win3

c_win_tot## [1] 0.2916667- Louana has a 58.33% chance of winning if the game is limited to three draws.

- Colin has a 29.17% chance of winning if the game is limited to three draws.

Game limited to 5 draws

Now if we compute the probabilities as if the game was limited to 5 draws and generalize the computation to see the pattern even more clearly, we have:

# Louana winning

l_win_tot <- ((tie^0) * l_win) +

((tie^1) * l_win) +

((tie^2) * l_win) +

((tie^3) * l_win) +

((tie^4) * l_win)

l_win_tot## [1] 0.6458333# Colin winning

c_win_tot <- ((tie^0) * c_win) +

((tie^1) * c_win) +

((tie^2) * c_win) +

((tie^3) * c_win) +

((tie^4) * c_win)

c_win_tot## [1] 0.3229167- Louana has a 64.58% chance of winning if the game is limited to 5 draws.

- Colin has a 32.29% chance of winning if the game is limited to 5 draws.

Game limited to 100 draws

We could continue like this for a long time, but for now let’s compute it for up to 100 draws, using a for loop. Using a for loop is necessary here in order to avoid to copy-paste our computations a hundred times.

For the ease of illustration, we compute only the probability of winning for Louana. We will show later on how the probability for Colin can easily be computed.

n_draws <- 100 # number of draws

l_win_tot <- c() # set empty vector

for (i in 1:n_draws) {

l_win_tot[i] <- ((tie^(i - 1)) * l_win) # prob of Louana winning up to n_draws

print(paste0("Draw ", i, ": ", sum(l_win_tot))) # print sum of winning up to n_draws

}## [1] "Draw 1: 0.333333333333333"

## [1] "Draw 2: 0.5"

## [1] "Draw 3: 0.583333333333333"

## [1] "Draw 4: 0.625"

## [1] "Draw 5: 0.645833333333333"

## [1] "Draw 6: 0.65625"

## [1] "Draw 7: 0.661458333333333"

## [1] "Draw 8: 0.6640625"

## [1] "Draw 9: 0.665364583333333"

## [1] "Draw 10: 0.666015625"

## [1] "Draw 11: 0.666341145833333"

## [1] "Draw 12: 0.66650390625"

## [1] "Draw 13: 0.666585286458333"

## [1] "Draw 14: 0.6666259765625"

## [1] "Draw 15: 0.666646321614583"

## [1] "Draw 16: 0.666656494140625"

## [1] "Draw 17: 0.666661580403646"

## [1] "Draw 18: 0.666664123535156"

## [1] "Draw 19: 0.666665395100911"

## [1] "Draw 20: 0.666666030883789"

## [1] "Draw 21: 0.666666348775228"

## [1] "Draw 22: 0.666666507720947"

## [1] "Draw 23: 0.666666587193807"

## [1] "Draw 24: 0.666666626930237"

## [1] "Draw 25: 0.666666646798452"

## [1] "Draw 26: 0.666666656732559"

## [1] "Draw 27: 0.666666661699613"

## [1] "Draw 28: 0.66666666418314"

## [1] "Draw 29: 0.666666665424903"

## [1] "Draw 30: 0.666666666045785"

## [1] "Draw 31: 0.666666666356226"

## [1] "Draw 32: 0.666666666511446"

## [1] "Draw 33: 0.666666666589056"

## [1] "Draw 34: 0.666666666627862"

## [1] "Draw 35: 0.666666666647264"

## [1] "Draw 36: 0.666666666656966"

## [1] "Draw 37: 0.666666666661816"

## [1] "Draw 38: 0.666666666664241"

## [1] "Draw 39: 0.666666666665454"

## [1] "Draw 40: 0.66666666666606"

## [1] "Draw 41: 0.666666666666364"

## [1] "Draw 42: 0.666666666666515"

## [1] "Draw 43: 0.666666666666591"

## [1] "Draw 44: 0.666666666666629"

## [1] "Draw 45: 0.666666666666648"

## [1] "Draw 46: 0.666666666666657"

## [1] "Draw 47: 0.666666666666662"

## [1] "Draw 48: 0.666666666666664"

## [1] "Draw 49: 0.666666666666666"

## [1] "Draw 50: 0.666666666666666"

## [1] "Draw 51: 0.666666666666666"

## [1] "Draw 52: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 53: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 54: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 55: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 56: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 57: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 58: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 59: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 60: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 61: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 62: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 63: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 64: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 65: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 66: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 67: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 68: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 69: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 70: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 71: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 72: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 73: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 74: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 75: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 76: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 77: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 78: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 79: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 80: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 81: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 82: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 83: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 84: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 85: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 86: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 87: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 88: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 89: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 90: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 91: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 92: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 93: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 94: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 95: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 96: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 97: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 98: 0.666666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 99: 0.666666666666667"

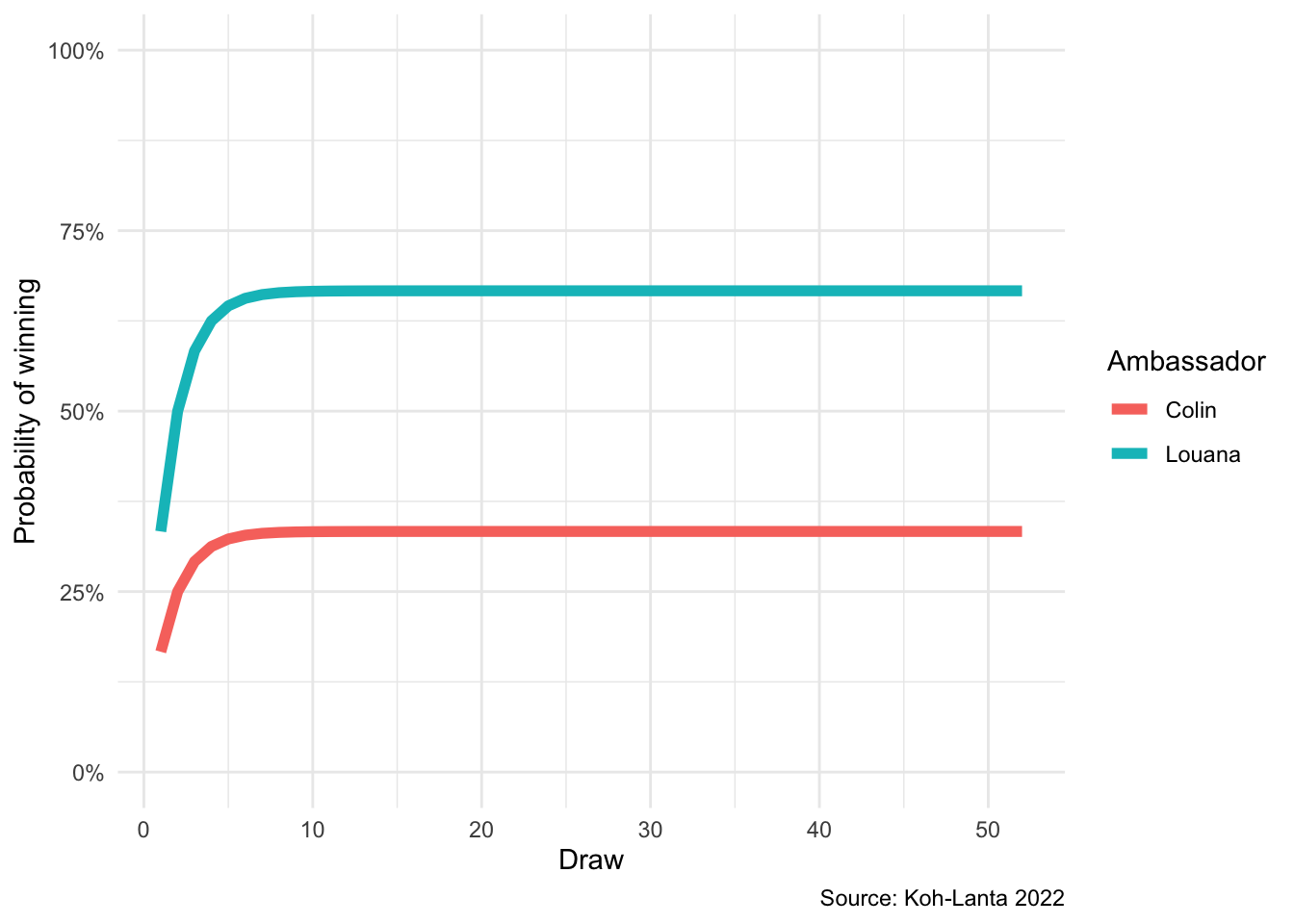

## [1] "Draw 100: 0.666666666666667"The probabilities found up to draw 1, 3 and 5 are coherent with what we found in the previous sections. Moreover, we see that from draw 52 onwards, the probability of Louana winning remains constant at 66.67%. This is referred as the limit.

Game limited to the number of necessary draws

Without printing the results of the above for loop, we do not know how many draws are necessary to reach the limit.

Let’s now try to include the information about the number of necessary draws in order to avoid computing unnecessary draws:

n_draws <- 9999 # initial number of draws, set intentionally to a high number

p_tie <- c() # set empty vector for prob of ties

l_win_tot <- c() # set empty vector for prob of Louana winning

# find number of necessary draws:

for (i in 1:n_draws) {

p_tie[i] <- tie^i # prob of tie for each draw

limit_ndraws <- sum(p_tie > 2.2e-16) # number of necessary draws

}

# compute Louana winning probabilities with the smallest number of necessary draws

for (i in 1:limit_ndraws) {

l_win_tot[i] <- ((tie^(i - 1)) * l_win) # prob of Louana winning up to limited number of draws

print(paste0("Draw ", i, ": ", sum(l_win_tot))) # sum of winning up to limited number of draws

}## [1] "Draw 1: 0.333333333333333"

## [1] "Draw 2: 0.5"

## [1] "Draw 3: 0.583333333333333"

## [1] "Draw 4: 0.625"

## [1] "Draw 5: 0.645833333333333"

## [1] "Draw 6: 0.65625"

## [1] "Draw 7: 0.661458333333333"

## [1] "Draw 8: 0.6640625"

## [1] "Draw 9: 0.665364583333333"

## [1] "Draw 10: 0.666015625"

## [1] "Draw 11: 0.666341145833333"

## [1] "Draw 12: 0.66650390625"

## [1] "Draw 13: 0.666585286458333"

## [1] "Draw 14: 0.6666259765625"

## [1] "Draw 15: 0.666646321614583"

## [1] "Draw 16: 0.666656494140625"

## [1] "Draw 17: 0.666661580403646"

## [1] "Draw 18: 0.666664123535156"

## [1] "Draw 19: 0.666665395100911"

## [1] "Draw 20: 0.666666030883789"

## [1] "Draw 21: 0.666666348775228"

## [1] "Draw 22: 0.666666507720947"

## [1] "Draw 23: 0.666666587193807"

## [1] "Draw 24: 0.666666626930237"

## [1] "Draw 25: 0.666666646798452"

## [1] "Draw 26: 0.666666656732559"

## [1] "Draw 27: 0.666666661699613"

## [1] "Draw 28: 0.66666666418314"

## [1] "Draw 29: 0.666666665424903"

## [1] "Draw 30: 0.666666666045785"

## [1] "Draw 31: 0.666666666356226"

## [1] "Draw 32: 0.666666666511446"

## [1] "Draw 33: 0.666666666589056"

## [1] "Draw 34: 0.666666666627862"

## [1] "Draw 35: 0.666666666647264"

## [1] "Draw 36: 0.666666666656966"

## [1] "Draw 37: 0.666666666661816"

## [1] "Draw 38: 0.666666666664241"

## [1] "Draw 39: 0.666666666665454"

## [1] "Draw 40: 0.66666666666606"

## [1] "Draw 41: 0.666666666666364"

## [1] "Draw 42: 0.666666666666515"

## [1] "Draw 43: 0.666666666666591"

## [1] "Draw 44: 0.666666666666629"

## [1] "Draw 45: 0.666666666666648"

## [1] "Draw 46: 0.666666666666657"

## [1] "Draw 47: 0.666666666666662"

## [1] "Draw 48: 0.666666666666664"

## [1] "Draw 49: 0.666666666666666"

## [1] "Draw 50: 0.666666666666666"

## [1] "Draw 51: 0.666666666666666"

## [1] "Draw 52: 0.666666666666667"Final winning probabilities

Remember that the initial question was:

What is the probability of winning the game for each ambassador?

The probability that Louana wins the game can easily be extracted as follows:

sum(l_win_tot)## [1] 0.6666667And since the game only stops when there is a winner, the sum of the winning probabilities for Louana and Colin must be equal to 1, so the probability that Colin wins the game is:

c_win_tot <- 1 - sum(l_win_tot)

c_win_tot## [1] 0.3333333To summarize:

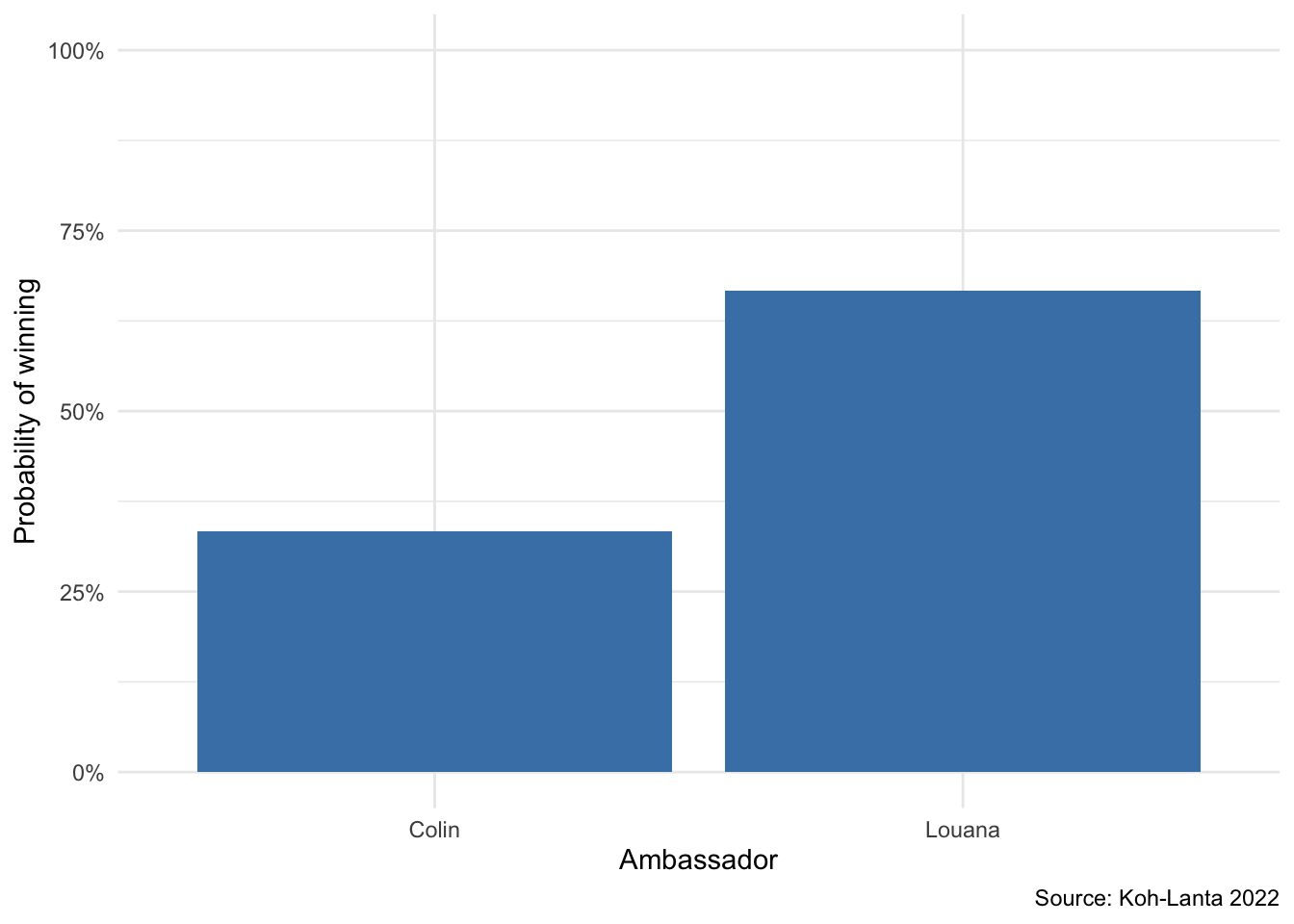

- Louana has 66.67% chance to win the ambassadors’ game.

- Colin has 33.33% chance to win the ambassadors’ game.

Visual representations

To visualize the probabilities for each ambassador, we miss the probabilities of winning for Colin so let’s compute them first:

c_win_tot <- c() # set empty vector for prob of Colin winning

# compute Colin winning probabilities with the smallest number of necessary draws

for (i in 1:limit_ndraws) {

c_win_tot[i] <- ((tie^(i - 1)) * c_win) # prob of Colin winning

print(paste0("Draw ", i, ": ", sum(c_win_tot))) # print sum of winning

}## [1] "Draw 1: 0.166666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 2: 0.25"

## [1] "Draw 3: 0.291666666666667"

## [1] "Draw 4: 0.3125"

## [1] "Draw 5: 0.322916666666667"

## [1] "Draw 6: 0.328125"

## [1] "Draw 7: 0.330729166666667"

## [1] "Draw 8: 0.33203125"

## [1] "Draw 9: 0.332682291666667"

## [1] "Draw 10: 0.3330078125"

## [1] "Draw 11: 0.333170572916667"

## [1] "Draw 12: 0.333251953125"

## [1] "Draw 13: 0.333292643229167"

## [1] "Draw 14: 0.33331298828125"

## [1] "Draw 15: 0.333323160807292"

## [1] "Draw 16: 0.333328247070312"

## [1] "Draw 17: 0.333330790201823"

## [1] "Draw 18: 0.333332061767578"

## [1] "Draw 19: 0.333332697550456"

## [1] "Draw 20: 0.333333015441895"

## [1] "Draw 21: 0.333333174387614"

## [1] "Draw 22: 0.333333253860474"

## [1] "Draw 23: 0.333333293596903"

## [1] "Draw 24: 0.333333313465118"

## [1] "Draw 25: 0.333333323399226"

## [1] "Draw 26: 0.33333332836628"

## [1] "Draw 27: 0.333333330849806"

## [1] "Draw 28: 0.33333333209157"

## [1] "Draw 29: 0.333333332712452"

## [1] "Draw 30: 0.333333333022892"

## [1] "Draw 31: 0.333333333178113"

## [1] "Draw 32: 0.333333333255723"

## [1] "Draw 33: 0.333333333294528"

## [1] "Draw 34: 0.333333333313931"

## [1] "Draw 35: 0.333333333323632"

## [1] "Draw 36: 0.333333333328483"

## [1] "Draw 37: 0.333333333330908"

## [1] "Draw 38: 0.333333333332121"

## [1] "Draw 39: 0.333333333332727"

## [1] "Draw 40: 0.33333333333303"

## [1] "Draw 41: 0.333333333333182"

## [1] "Draw 42: 0.333333333333258"

## [1] "Draw 43: 0.333333333333295"

## [1] "Draw 44: 0.333333333333314"

## [1] "Draw 45: 0.333333333333324"

## [1] "Draw 46: 0.333333333333329"

## [1] "Draw 47: 0.333333333333331"

## [1] "Draw 48: 0.333333333333332"

## [1] "Draw 49: 0.333333333333333"

## [1] "Draw 50: 0.333333333333333"

## [1] "Draw 51: 0.333333333333333"

## [1] "Draw 52: 0.333333333333333"We create a dataset with the probabilities for both ambassadors:

dat <- data.frame(

Draw = rep(1:limit_ndraws, 2),

Probability = c(cumsum(l_win_tot), cumsum(c_win_tot)),

Ambassador = c(rep("Louana", limit_ndraws), rep("Colin", limit_ndraws))

)We can now visualize these probabilities up to the number of necessary draws:

# load package

library(ggplot2)

# plot

ggplot(dat) +

aes(x = Draw, y = Probability, colour = Ambassador) +

geom_line(linewidth = 2L) +

labs(

y = "Probability of winning",

caption = "Source: Koh-Lanta 2022"

) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent_format(accuracy = 1), limits = c(0, 1)) +

theme_minimal()

But I believe the most appropriate plot to answer the initial question is with a barplot:

# create dataset

dat_barplot <- data.frame(

Ambassador = c("Louana", "Colin"),

Probability = c(sum(l_win_tot), sum(c_win_tot))

)

# plot

ggplot(data = dat_barplot, aes(x = Ambassador, y = Probability)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity", fill = "steelblue") +

labs(

y = "Probability of winning",

caption = "Source: Koh-Lanta 2022"

) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent_format(accuracy = 1), limits = c(0, 1)) +

theme_minimal()

Coded into a function

Let’s try to implement this problem in a function to be able to reuse it with other initial probabilities.

With:

p_aandp_bdenoting, respectively, the probability that ambassador A and ambassador B draw a white ball,n_drawsdenoting the maximum number of draws that is allowed (default = 9999),

we have the following function:

ambassadors_game <- function(p_a, p_b, n_draws = 9999) {

q_a <- (1 - p_a)

q_b <- (1 - p_b)

a_win <- q_b * p_a

b_win <- q_a * p_b

tie <- (p_a * p_b) + (q_a * q_b)

p_tie <- c() # set empty vector for prob of ties

a_win_tot <- c() # set empty vector for prob of A winning

b_win_tot <- c() # set empty vector for prob of B winning

# find number of necessary draws:

for (i in 1:n_draws) {

p_tie[i] <- tie^i # prob of tie for each draw

limit_ndraws <- sum(p_tie > 2.2e-16) # number of necessary draws

}

# compute A and B winning probabilities with the smallest number of necessary draws:

for (i in 1:limit_ndraws) {

a_win_tot[i] <- ((tie^(i - 1)) * a_win) # prob of A winning up to limited number of draws

b_win_tot[i] <- ((tie^(i - 1)) * b_win) # prob of B winning up to limited number of draws

}

# save P(A), P(B) and number of necessary draws:

res <- list(

"p_a" = sum(a_win_tot),

"p_b" = sum(b_win_tot),

"ndraws" = limit_ndraws

)

# print results:

return(res)

}We test the function to see if it matches results found above.

First, if both ambassadors have identical urns as it was the case before the 2022 season:

ambassadors_game(

p_a = 1 / 2,

p_b = 1 / 2

)## $p_a

## [1] 0.5

##

## $p_b

## [1] 0.5

##

## $ndraws

## [1] 52The game is indeed fair, with a 50% chance of winning for each ambassador.

Second, with the urns presented to Louana and Colin, but for the first draw only (setting arbitrarily that Louana is ambassador A and Colin is ambassador B):

# first draw only

ambassadors_game(

p_a = 1 / 2,

p_b = 1 / 3,

n_draws = 1

)## $p_a

## [1] 0.3333333

##

## $p_b

## [1] 0.1666667

##

## $ndraws

## [1] 1Third, still with the urns presented to Louana and Colin, but for a game limited to exactly 3 and 5 draws:

# up to 3 draws

ambassadors_game(

p_a = 1 / 2,

p_b = 1 / 3,

n_draws = 3

)## $p_a

## [1] 0.5833333

##

## $p_b

## [1] 0.2916667

##

## $ndraws

## [1] 3# up to 5 draws

ambassadors_game(

p_a = 1 / 2,

p_b = 1 / 3,

n_draws = 5

)## $p_a

## [1] 0.6458333

##

## $p_b

## [1] 0.3229167

##

## $ndraws

## [1] 5And now, the final verification with the real situation of Louana and Colin in Koh-Lanta 2022:

# Koh-Lanta 2022 situation

out <- ambassadors_game(

p_a = 1 / 2,

p_b = 1 / 3

)

out## $p_a

## [1] 0.6666667

##

## $p_b

## [1] 0.3333333

##

## $ndraws

## [1] 52All results match the ones presented above.

(Note that the probabilities for each ambassador can be extracted as follows:)

# prob ambassador A

out$p_a## [1] 0.6666667# prob ambassador B

out$p_b## [1] 0.3333333Conclusion

The initial question, coming from the television show Koh-Lanta, was “what is the probability of winning for each participant if they play the ambassadors’ game?”.

In this article, we have shown how to compute these probabilities. Moreover, we have illustrated the process of how a simple probability problem could be generalized to suit many real life situations, and how a for loop and a function could be used to implement a real life situation into R.

Last but not least, I would like to focus on something Denis Brogniart (the well-known presenter of the show) said just after the two ambassadors came back to the island to announce their choice to the other adventurers. He mentioned that, due to the punishment afflicted to the yellow tribe, there was a difference of chances of 16% between Louana and Colin.

This comes naturally from the following two situations:

First situation:

- Louana has a 50% chance of picking a white ball.

- Colin has a 33.33% chance of picking a white ball.

- The difference is 50 - 33.33 = 16.67%, rounded to 16%.

Or, if the game is limited to the first draw only:

Second situation:

- Louana has 33.33% chance of winning the game.

- Colin has a 16.67% chance of winning the game.

- The difference is 33.33 - 16.67 = 16.66%, rounded to 16%.

It is true that, seeing the problem from those two angles, the difference is ~16%. Denis Brogniart is right in mentioning this 16% difference.

However, the difference of chances between the two ambassadors is larger if we see the game from a broader perspective. The rules of the game say that it stops only when there is a winner. From that point of view, as demonstrated above:

- Louana has 66.67% chance of winning the game.

- Colin has 33.33% chance of winning the game.

In this situation, the difference in probability of winning between the 2 ambassadors is 66.67 - 33.33 = 33.34%!

I must admit that I was not expecting such a large difference between the two ambassadors. Seeing the ambassadors’ game from that perspective looks different to what we were told, or to what we thought before actually computing the probabilities. (Denis Brogniart, if you happen to read this, feel free to let me know whether this relatively large difference was intended or not.)

For those of you who do not watch the show: upon the return of the ambassadors on the island with all adventurers, Colin has been heavily criticized by the members of his tribe. His decision not to play the ambassadors’ game (and the decision to eliminate one member of his tribe with the aim of saving himself) was seen as a betrayal. As a consequence of this, he was eliminated by the reunited tribe directly after that episode.

I am going to conclude this article with the following question:

If you were an ambassador in the 2022 Koh-Lanta season and given that now you know the exact probabilites of winning for each tribe, what would you have done?

Thanks for reading.

As always, if you have any question related to the topic covered in this article, please add it as a comment so other readers can benefit from the discussion.

We will never know if he would have played the game if the chances of winning were equal for both ambassadors. Since I started to watch this television show, I have never seen any ambassadors’ negotiation leading to the ambassadors’ game, they all ended with the designation of an adventurer.↩︎

And to be honest, I wanted to compute these probabilities because while I was watching the show with my girlfriend, she looked at me and asked “what are the probabilities for each of them?”. I am now able to give her a precise answer.↩︎

Liked this post?

- Get updates every time a new article is published (no spam and unsubscribe anytime)

- Support the blog

- Share on: